Trapwords is a fantasy themed word-guessing game which takes a twist on the classic game Taboo. In this article, I’ll explain the game, dive into some basic strategy, and close with more advanced strategies you can try during your next game night.

Rules of the Game

Two teams compete in a race to get to the end of the dungeon and beat the monster lurking there. To progress through the dungeon, you must describe a given word to your teammates (which we’ll call the target), but you have to do so without saying the word itself or a set of related words, called “trap words.” The unique part is that the other team sees the target before you give clues for it, and then chooses which trap words you can’t say. To make it even more interesting, you don’t get to see the trap words before you have to start giving your clues!

Each round, your teammates have thirty seconds and five guesses to guess the target. If you say a trap word, your turn ends. If your team avoids all the trap words and gets the target right, you move forward one tile. The first team to get to the tile with the monster has to get one more target word right, but this time with an added restriction that the monster gives. If they get it right, they win!

Trap words must be nouns, verbs, or adjectives. As each team progresses through the dungeon, the amount of trap words the opposing team writes down increases (denoted by the number on each tile). Additionally, the team in the lead must pass through various curses which restrict them.

Basic Strategy

At first, the strategy seems obvious. Let’s say you are writing three trap words for your opponent, and they have a target of “pencil.” An intuitive set of trap words might be “write,” “yellow,” and “paper.” While these are reasonable, your opponent will most likely expect that you’ve written down some or all of these words and attempt to avoid them. They may say something like “This is the thing that has an eraser at the end of it” or “This is the thing that makes marks on the thin white sheets” or even a more divergent “You use these when you’re taking standardized tests.” To try to prevent this, you can trap words to block these divergent paths, like “eraser,” “mark,” or “test.” If you do that though, they can say “This is the yellow thing you write with” for an extremely easy clue.

This then is the interesting part of the game. If you trap very obvious words, your opponent will guess you’ve trapped those and avoid them. If you trap divergent words, you potentially allow your opponent a very easy clue. Something to note is that your opponents can’t see your trap words before they give their clues, so they can’t base any decisions off of the words you trap. This may seem obvious, but it leads to an interesting conclusion: the game is more about predicting the words your opponents are going to say then it is about blocking the words they can say. Your task in writing trap words is not “what words can I trap that will block them from getting the clue?” but simply “what words do I think they are going to say?” From the trap word side, the two primary factors in this prediction are:

1) How useful is this word for describing the target?

2) How likely is my opponent to avoid using this word because they expect me to trap it?

As the clue giver, you are weighing two very similar factors in deciding which words to say in your clues:

1) How useful is this word for describing my target?

2) How likely is my opponent to have trapped this word?

One technique you can use for predicting what your opponents are going to say is to think about what you would say if you were clue giving and saw this word as the target. That is, you can ask yourself “if I saw this word and had to give clues, how would I start?” Asking this to yourself helps you see how people might try to be divergent with their clues.

Curses

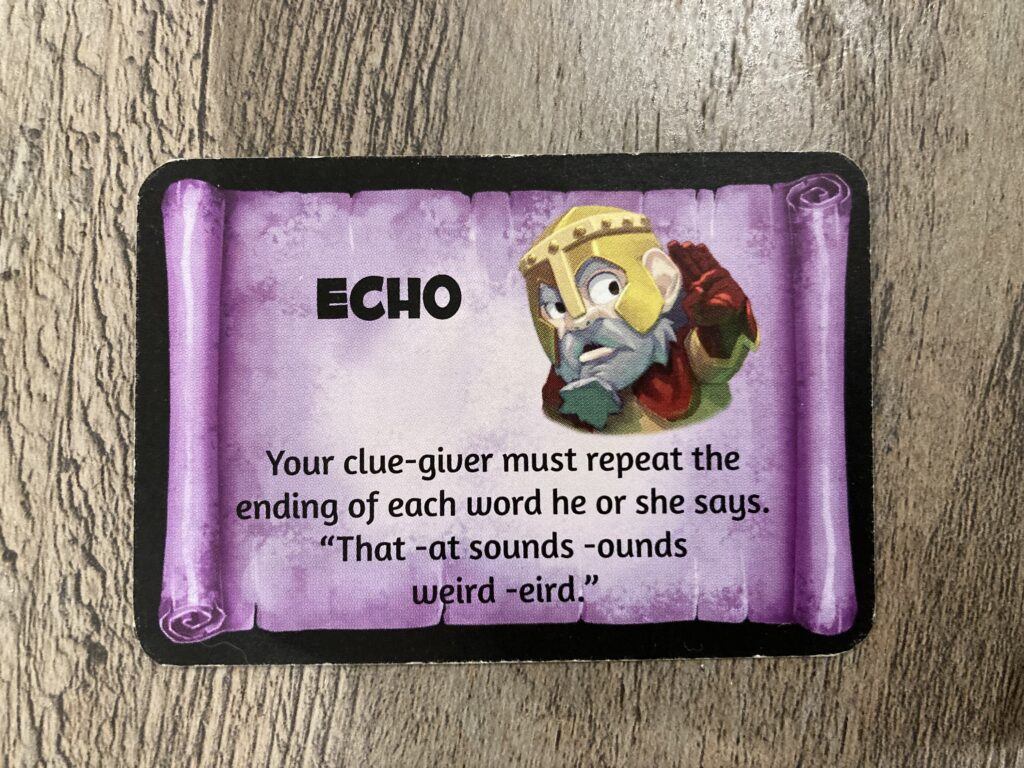

Curses, which appear on the second and fourth tile of the board, add a unique element to the game. The first team that gets to this tile has to play with the curse for one round. Echo is one example of a curse:

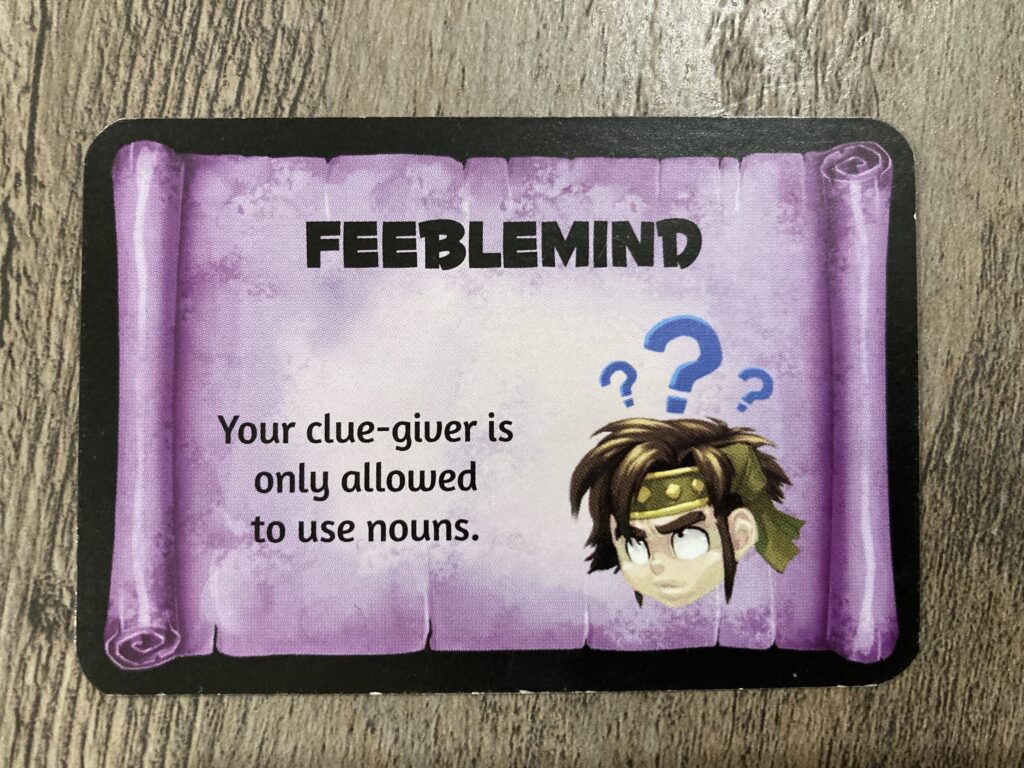

This makes the round harder, as not only do you have to use mental energy trying to remember your restriction, but it also takes additional time to say the echoes. While this curse makes it harder for the giving team, it probably won’t affect how the other team chooses their trap words. Now take a look at the curse Feeblemind:

This curse makes the round harder for many reasons. The set of words you can say is much smaller, so the baseline difficulty of getting the target is higher. Additionally, the trapping team only needs to trap nouns, allowing them to trap a proportionally larger amount of the words that you can say. Finally, it’s harder to be divergent when you can only say nouns, so the trapping team can trap more obvious words. All in all, it is very challenging to get the target while playing with this curse.

Because the curses affect the team who gets to that tile first, they end up adding a restriction to the team in the lead. In this way, they not only make the game more fun, but also serve as a catch-up mechanic to slow down the team in the lead.

Monsters

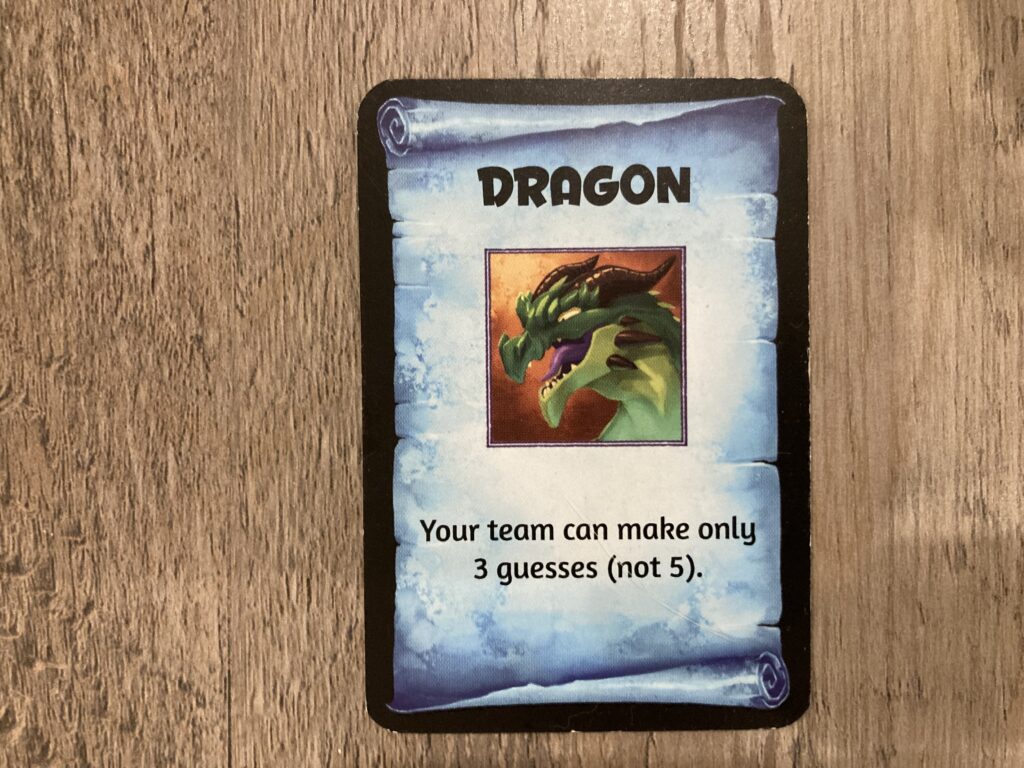

To win, you must defeat the monster, which functions similarly to the curses by adding a restriction to giving team. There are five unique monsters (each with an extra hard version as well) which make the round more difficult. The simplest monster is the dragon:

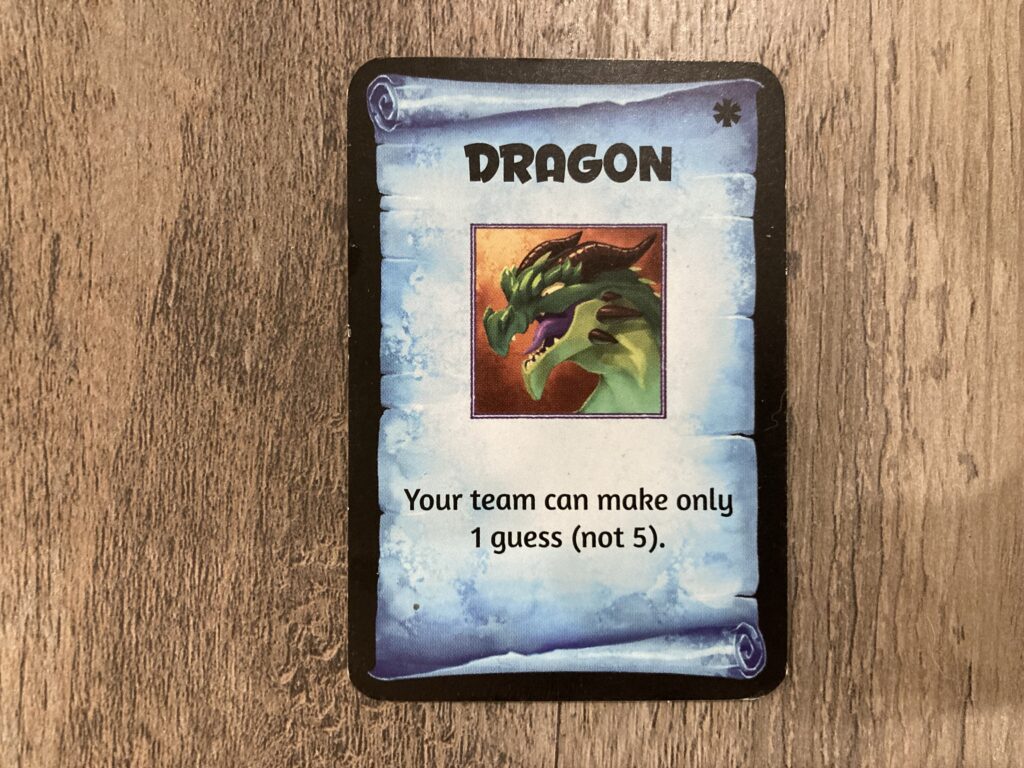

It makes the round harder and prompts a slight change in strategy. The giving team is likely to want to give more obvious and direct clues, which means the trapping team is more inclined to write down obvious hints. This is taken to the extreme with the hard version of the dragon:

With only one guess you have to be very precise with your clues, and the trapping team can trap nearly entirely obvious words as you have such little wiggle room. Another monster is the demon which changes the game in a different way:

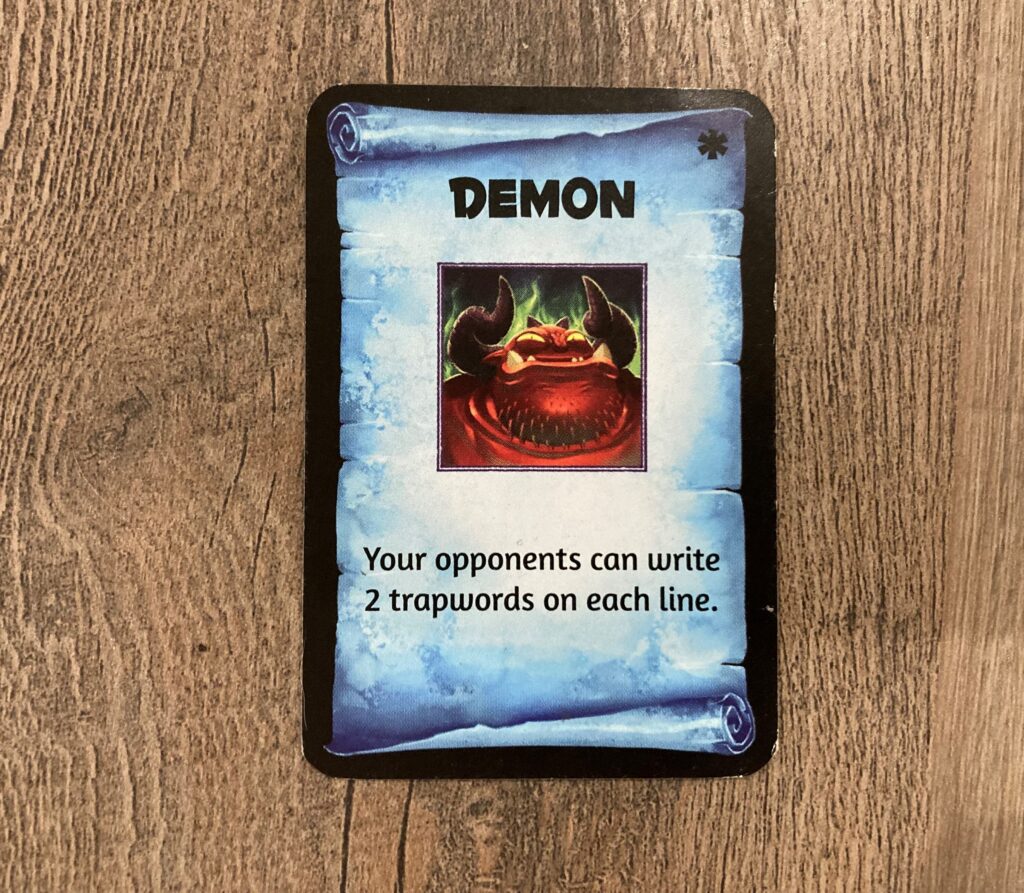

The demon gives your opponent 1.5x as many trap words as they would normally have. This changes the dynamic in that your opponent may be inclined to trap more obvious words given they can cover such a large space with them. The hard version of the demon takes this to another level:

This is incredibly challenging! The game comes with tiles numbered 1-10, so on the hardest tile this means your opponent can trap 20 words! I have tried this and it’s almost hard to come up with words to trap because you feel like you’ve already covered everything they could possibly say once you get to 15 or so. Beating this monster almost always requires a creative and divergent approach.

Only the team on the monster tile has to play with the restriction, so they function similarly to curses in giving the team that’s behind time to catch up. The monsters add variability to the game and make the final round more fun and exciting.

Advanced Strategy

Let’s re-visit the strategy part of the game. First, we’ll simplify it into saying there are two types of clues: “straightforward clues” (SC) and “divergent clues” (DC). Straightforward clues are the most obvious ways to describe the target, and divergent clues are the least intuitive ways to describe the target. SC are better in general as they’re more descriptive, so your opponents will tend towards trapping words to block those. This means they are not trapping words used in DC, so you can use those with less fear of being trapped. There is a tradeoff to using DC however, which is that DC give less information about the target. Remember, the game is not about not getting trapped, the game is about giving clues which allow your team to successfully guess the target. While a part of this is not being trapped, another part is being able to give descriptive clues in the short amount of time given.

Using DC, you have a much harder time of this than you do using SC. In addition, if you only use DC, your opponents will notice. They will then start to trap words that cover DC and leave SC free. This means using SC will not only increase your probability of getting the target right, they will actually decrease the probability you get trapped. Of course, if you then adjust and tend towards using more SC your opponents will also adjust and trap words used in SC. This then pushes the balance back to DC as you are more likely to be trapped if you keep using SC.

The key then is to use some combination of SC and DC. This way, your opponent is limited in how to trap you: if they trap entirely DC, they’ll miss words for SC, but if they trap entirely SC, they’ll miss words for DC. To take this even further, there is an order in which it is best to give these clues. The importance of giving descriptive clues that allow your team to guess the target versus giving clues that won’t be trapped shifts throughout a turn. That is, when you have 25 seconds left and five guesses, you are more concerned with getting trapped than you are not getting the target, but when you have five seconds left and one guess you are more concerned with not getting the target than getting trapped. This means the optimal strategy is to start your turn with DC and then pivot to SC as you run out of time and/or guesses.

Game Theory and Exploitive Play

These concepts are closely related to the idea of a “Mixed Strategy Nash Equilibrium” from game theory. The idea is that if you play perfectly predictably, as in always give SC or DC, then your opponent can exploit you and only trap words in that category. In order to avoid this you must use a mixed strategy with both types of clues, thus making it not obvious to your opponent which words to trap.

There is no clear optimal ratio of SC to DC to use, and the ratio will vary from player to player. The way to move towards your optimal ratio as you play is to see how you fail as a clue giver. That is, if your failures are more often from getting trapped than from your team not getting the target, you should try to use more DC. If your failures are instead more from your team not being able to guess the target than from getting trapped, you should try to use more SC. While this optimal strategy of mixing between SC and DC is clear, it is pretty hard to implement perfectly in practice. This means that you should try to notice and exploit your opponent’s imperfect tendencies.

For example, let’s say you notice your opponent’s DC are always opposites. That is, if they had the target “night” they’d say “the opposite of day” or if they had the target “corpse” they’d say “the opposite of something living.” If they then had the target “giant,” you could try to exploit this pattern by trapping words like “tiny” or “small.” An even more ambitious and creative exploitative play would be to write down the word “opposite” itself. Exploitative play on the clue giving side is to notice that your opponents are consistently trapping mostly SC or mostly DC, and then giving clues in the category they didn’t trap. These tricks probably only work once or twice, but they can be effective tools if you know your opponents have consistent patterns in their play.

Words as a Set

Another interesting facet is that it’s better to think of your trap words as a set, not just independent words. To see this, let’s re-visit the idea that your goal is to predict what your opponents are going to say. That’s not entirely true. Let’s say you’ve written all your trap words but one. The only times this last trap word matters are when your opponent says it on a path that leads to their team guessing the target that hasn’t already been trapped. For example, let’s say the target is “quarter.” You think there’s some possibility they’ll describe this word by mentioning what the “tooth fairy” gives out. In this case you would only need to write one of “tooth” or “fairy”, but not both. Both words are pretty divergent from the rest of the clues one could give for quarter, so they only really trap the times your opponent goes the “tooth fairy” route. If they go that route, they will most likely say both “tooth” and “fairy.” This means if you’ve already written down fairy (probably the slightly better of the two to write) then writing down tooth has very little additional benefit as few paths contain tooth and not fairy while still leading to the opposing team guessing the target.

Relatedly, let’s say you know your opponent tends towards insanely divergent clues. You may have an incredible read on them and are 85% confident they’ll say some super divergent word, but you’re 99% confident that if they say that word they’re on such a bad track that their team will never get the target. In this case even though the trap word may end their turn it’s not actually worth trapping as their turn was going to end in failure anyways. You only need to trap words that they give on the way to success; you gain nothing from trapping a word they use when their turn would have ended in failure anyways.

Summary

That’s Trapwords! A game with simple rules but very deep strategy. I love the game as it’s very accessible, has enough variance to be always interesting, all while still providing a lot of strategic depth for both the clue-giver and trap word writer.

Subscribe Now

Get each new post sent straight to your inbox