Basic Overview

Magic: The Gathering is an incredibly popular strategy dueling card game with over 50 million players worldwide, bringing in over $1 billion in revenue annually for Hasbro[1]. It originated the concept of a collectible card game where players open boosters (like baseball card packs) to acquire new cards.

There are many different formats. Some formats allow you to construct your deck beforehand using defined construction rules, while others don’t allow you to know what cards you’ll be using until the tournament begins. The game can be played live and in person with physical cards or digitally on MTG Arena.

A game is played out over the course of alternating turns. On a given turn, there are many possible moves a player can make while advancing through several different phases (draw phase, attack phase, etc.). Playing cards costs “mana,” which is generally obtained by playing lands that can be used once per turn. The goal is to win, usually by reducing one’s opponent’s life total from 20 to 0.

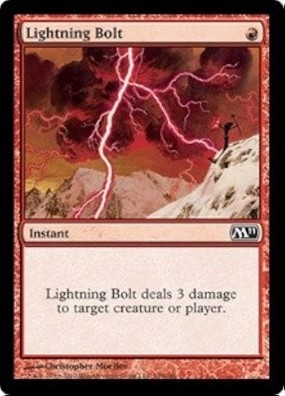

At each point in a turn, there is an opportunity for one’s opponent to react to the play the active player has made. For example: I cast the spell “Lightning Bolt” targeting my opponent’s “Grizzly Bear” creature, then they have the opportunity to respond, perhaps playing “Counterspell” to negate my play or a “Giant Growth” to make their “Grizzly Bear” big enough to survive the attack. I might then respond to their spell with one of my own, and so on.

As the board fills with more cards, the number of possible interactions increases. Moreover, the hidden information as to what your opponent has in their hand (and might draw on their turn) adds to the complexity of your decision-making.

In this article, I’ll focus specifically on a few key concepts regarding interactions and information that regularly appear in live play.

Drawing Cards

Each turn, a player must draw a card from their deck. Additionally, various effects can trigger extra card draws.

Anytime you draw a card, it’s best to shuffle your hand afterwards. Why? Well, as in poker, an observant opponent will watch to see how you react to different events over the course of the game to create a mental framework for a range of cards you might plausibly have. They will attempt to reverse-engineer your hand based on your reactions. If you never shuffle your hand, you are giving your opponent more information. Your opponent can determine whether you just drew the card you played or if you’ve had it all along

The less certain an opponent is about what’s in your hand, the tougher it will be for them to play perfectly. They might play a card that you have the perfect answer for or hold back on a devastating play out of fear that you have a countermeasure in hand.

The mere act of forcing your opponent to think harder can be a strategic move on your part. A Magic game can be a test of mental endurance, and tiring one’s opponent by forcing them to think more might pay off later in the game when they make a suboptimal play after running out of willpower to think through all the possibilities.

Along these lines, it may be better sometimes not to play a card you have drawn if it will have very little effect on the game. There is a value to a card remaining in hand as a mystery rather than becoming open information on the board.

Time

Another way you might unwittingly give information to your opponent is in how much time you spend on various actions.

Using the earlier example where you have a “Grizzly Bear” creature and your opponent attempts to destroy it with “Lightning Bolt,” you might be tempted to immediately put the Bear in your discard pile if you have no possible response in hand. This allows you to move the turn along, and if it’s a tournament, rounds are timed. Still, this would be a poor play. It would be better to pause, even briefly, to make it seem as though you are considering a possible play for all the reasons mentioned in the previous section. You don’t want to make it too easy for your opponent to know you had nothing to stop their play, as that might be relevant later in the game.

Another example would be that you play a card that grants you a “Scry” effect, where you get to look at the top few cards of your deck and then decide whether to keep those cards on top (with the possibility to rearrange the order) or to move some or all of them to the bottom of your deck. If you see the exact card you need on top, you might be tempted to leave it there quickly since you got just what you needed! Or maybe all the cards on top were terrible, so you quickly move them all to the bottom. Either way, your opponent just got more information. It’s better to try to spend about the same amount of time whenever you use an effect like this, so they won’t be able to deduce anything from your speed of play.

Passing Priority

In live play, a common question for one’s opponent to ask is: “Are you done?”

They need to know that you have finished before they can proceed to the start of their turn.

Replying “yes” to this question is the chess equivalent of hitting your clock. The turn is over. If you are in a tournament setting, it is now too late to say, “Oh no, wait, I have one more thing to do!”

You should always respond to this question with the same answer: “No.”

Why? What if you really are done? What’s the harm in letting your opponent begin their turn?

The issue is that you are not ending the turn on your own terms, but rather at your opponent’s prompting.

It’s always possible that the question is innocent, and the opponent just wants to clarify if they can go. But…it’s also possible there is information in the question.

Perhaps there is a play the opponent is hoping you won’t notice, and they want to rush you past it. Or maybe they just want to limit your time in general by forcing you to make decisions faster than you want to, so you play more on autopilot than in a thoughtful, deliberate way.

It is better here to say “no,” try to take a fresh look at the board and your hand, and think about what else you might want to do. This can be difficult. If there is something you are missing, how do you catch it? I suggest reviewing what is on the board, looking at your life total and your opponent’s, and considering what other lines you might take other than what you had originally intended. If your opponent seems eager to start their turn, does that change anything?

Also, remember it is valuable to keep your opponent from knowing what you have. By saying “no” when asked if you are done, you are keeping the possibility alive that you have more to do. Even if this isn’t the case, it increases the range of possible hands you might have, making it more difficult for the other player to play optimally.

After this review, it’s then fine to go ahead and say: “Okay, now it’s your turn.”

Conclusion

Magic: The Gathering is a very rich, strategic game. In live play, there are many considerations to be accounted for to maximize your chances of emerging victorious. I couldn’t hope to cover them all in one article, but hopefully these initial points set you on a path to thinking about the information you give based on the actions you take at the playing table. Even if you don’t decide to try to make a run at the Magic Pro Tour, consider how this approach can also translate to other games and even life!

[1] Per Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic:_The_Gathering

Subscribe Now

Get each new post sent straight to your inbox